Photo copyright Phillipe Gaucher, 2008. The fruit sitting near the chick is from the tree itself.

Determining the diet of birds is difficult undertaking. Because predation is so difficult to observe in the field, a relatively unbiased way to gather data on food habits is to place a camera in the nest to record the types of food brought to chicks. In my literature search on Red-throated Caracaras, I had come upon several references of gut content examination from shot specimens [1], as well as some field observations by J.M. Thiollay [2] and Whittaker [3], but little in the way of quantifiable data on the diet of caracaras. Because my research project was on the adaptations of a specialist predator of social wasps, we needed to first determine whether Ibycter americanus was in fact a specialist!

There are lots of delicious wasps in the jungle, like these Apoica albimacula, but are the caracaras eating them?

In 2008, my field assistant Onour Moeri and I were extremely fortunate to discover a nest of Red-throated Caracaras not far from the Inselberg Camp of the Nouragues Station in Central French Guiana. They appeared to be nesting in a large bromeliad, 45 m up a Chrysophyllum lucentifolium tree. These big trees in the Sapotaceae produce a large hard fruit, that despite its copius latex, is a favourite food of spider monkeys (Ateles paniscus).

There were certainly lots of spiders coming to the tree every few days, raining down discarded fruits from high above. We evacuated the area as soon as they reached the tree, as the hard, heavy fruits were travelling very quickly when they hit the ground!

This find was a great breakthrough for us, as we now had a reliable focal point to find the birds and observe their behavior. We were extremely excited, because this was only the third nest ever observed by scientists, and as such was an amazing opportunity to gather data on the habits of the birds. We spent the first few weeks on the ground below the nest tree, watching with binoculars as adult birds arrived with food. We observed them bringing wasp nests and fruit, arriving roughly every half hour. This was not the most fun thing to do, as sitting still in the jungle looking up all day is actually kind of difficult, especially when it rains. The data we were getting was spotty and probably quite biased…Not good!

The nest bromeliad!

We also found another nest in 2009, in another bromeliad 40 m up a different tree. We have good reason to suspect it was made by the very same group. I am not showing any footage of this, due to its low quality! We got good data from it however.

Luckily, going above and beyond the call of duty, Philippe Gaucher (the technical director at Nouragues, and a good friend) was kind enough to track down some video recording equipment in Cayenne and bring it back for us to set up a nest camera. On Feb 2 he climbed the nest tree to install it. The nest contained a single caracara chick, which we later sexed as a female, via a genetic analysis from a plucked feather. The still pictures Philippe took up there were the very first (that I know of) ever taken of a Red-throated Caracara chick. Evidently, these caracaras had not constructed the nest at all, but rather had torn the bromeliad leaves to make a platform to lay an egg on. Like many insects and frogs, the Red-throated Caracaras are bromeliad breeders!

The photos also showed evidence of predation on both wasps and millipedes! We were extremely excited to have this equipment installed, and that very night we started getting video from the nest.

Philippe climbing the nest tree to install the camera.

Each evening, I would go down to the nest after dark (there were a lot of tarantulas I became quite familiar with) and lug the DVR and usually the 20 kg battery back up the hill. Then every morning before dawn, I would take the recharged battery down and replace the DVR for that day’s recordings. The setup involved a large plastic box, to shield the DVR from rain, plus a tarp to do more of the same thing. With the DVR running in the box, there was little danger of water damage (it was the rainy season), but to leave it there at night without power was out of the question. Unpowered electronic devices (that are not making heat) often succumb to the near 100% humidity of the rainforest.

The DVR in place under the tree. The tarp protects from falling fruit and rain, and the DVR stayed cosy in the Tupperware!

The camera in place over the bromeliad, about 1 m above the nest. Photo by Philippe Gaucher.

After a couple days of recording, we quickly discovered that the “waterproof” camera was less than watertight; our lens had fogged up with internal condensation. A whole day of wasted recording! Phillipe had flown back to Cayenne, so there was nothing for it but to go up the tree myself and fix the camera. I had trained in tree climbing back when I was an environmental activist, so I knew what to do, but still, this was a 45 m straight climb up to a spiky bromeliad, with possibly murderous birds protecting their nest.

The climb was exciting, though relatively uneventful, and I retrieved the camera and dried it out. Then, after jamming a silica gel dessicant pack into the housing, I carefully wrapped every threaded connection with Teflon tape. With the camera returned to the nest, we continued filming.

A Polybia nest brought via an overhead branch.

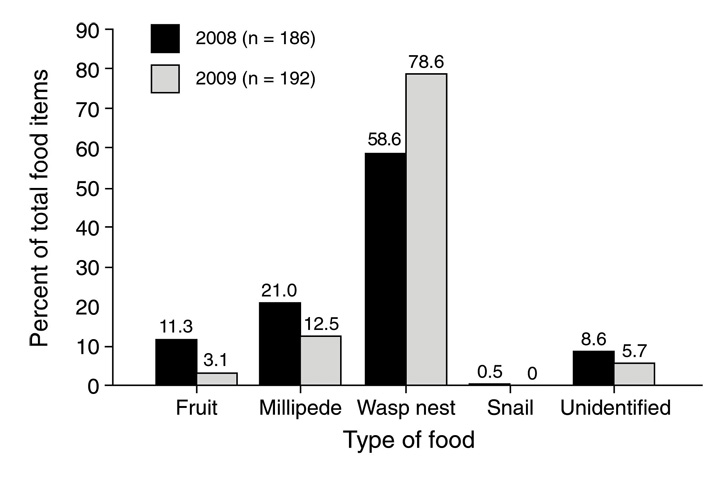

In total, we managed to get about 100 hours of recording done over 10 days. During that time, we recorded 186 items being brought to the chick, most of which were the nests of social wasps, but also fruits, millipedes and a single snail. Back in the lab, I watched these hours of footage, timing the arrivals and departures, the types of prey, and other aspects of the footage. I organized all of this in a database, which is the best way of storing large amounts of data and retrieving it in a format for analyses.

The chick receives a delivery of an Angiopolybia or Pseudopolybia nest. Notice how packed the brood comb is with larvae and pupae.

Breakdown of the diet over 2 years. Most of the items (and definitely most of the biomass) were the brood-filled nests of social wasps.

A large spirostreptid millipede is brought to the chick.

The large spirostreptid millipedes were brought intact, and were decapitated by the adults, after which they generally tried to feed bits to the chick. Usually, the chick ate very little or perhaps none of this material. These large millipedes are well-defended with a lot of noxious benzoquinones, which are toxic, irritating and carcinogenic compounds. My suspicion is that these are in some way related to chemical defense against ectoparasites, as some birds as well as capuchin monkeys are reported to anoint themselves with the millipedes’ secretions [4].

Onour with a millipede on a stick!

The nasty, nasty secretion from these docile animals. It burns the skin, and seems to stain it purple. Oh yeah, and then your skin smells of millipedes.

Though we had no birds marked, on a few occasions we saw more than two adults bringing prey to the chick, confirming Thiollay [2] and Whittaker’s [3] observations of cooperative breeding . In 2009 we captured and colour-banded four adults and were able to determine that as many as 6 and most likely 7 birds bringing prey to a single chick [5]! This is highly unusual in raptors, and another reason I love these caracaras so much. What kind of remarkable social system is this? Which individuals get to breed? Are all the helpers young from previous years (delayed dispersal) or are there joiners from other groups? We still do not know the answers to these questions, but I hope to find out in the future.

Two adults deliver fruit, while a third remains in the nest with the chick.

Watching the videorecordings of nesting behaviour has been one of the highlights of my career so far. Seeing this drama unfold for the very first time was so exciting; no one had observed this species ever before, and my job was to describe it to the world. What a treat! And to watch closely at all the magical moments in a young bird’s life was just priceless. Check out this caracara chick observing an insect flying overhead. The interest she shows in this event is so cool to see, and you get the notion that she is learning lessons every waking moment that will help her out when she is out foraging for herself.

This young caracara is a truly professional entomologist!

By March 17, we had no more time left in the field, and no one to continue the camera work. We had to take down the setup and get packed up to return to Canada. When I went up the tree to retrieve the camera, it was bittersweet, as we had succeeded in getting great data from our first field season, but our lovely caracara chick would grow up and fledge without us being there to see it. In just a few weeks of observation, she had already stolen our hearts.

Of course, I brought my camera up to take a farewell portrait.

Farewell, little caracara chick! Best of luck, and thanks for all the data! By the way, what is that on your beak?

A gorgeous Sabethes mosquito!

References