We have an expression “when the wolf is at the door” meaning that bad times are upon us, and poverty/ill health is looming. This implies a feeling of despair and anxiety, and when the wolf is at the door, it is likely that our hormonal systems reflect our stress.

So too with the wolves, when humans are at the door, so to speak. Recent research by Heather Bryan shows that both stress hormones and sex hormones seem to increase as a result of human persecution.

Dr. Bryan and her team quantified hormones in hair from wolves from populations which varied in the level of human persecution: tundra/taiga wolves from Nunavut and the Northwest territories, and boreal forest wolves from the Northwest territories and Alberta. The tundra/taiga wolves experience on the whole a greater level of persecution than those in the boreal forest, but Dr. Bryan also examined an outgroup of boreal wolves with high levels of persecution.

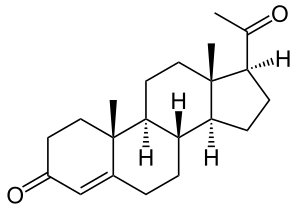

cortisol

Cortisol is a hormone which is produced under various stressful conditions, such as injury, starvation and social conflict. Tundra/taiga wolves had greater levels of these hormones than wolves from the boreal region. The increases associated with human hunting pressure could reflect changes in the social structure wrought by mortality of members of these tight-knit groups of animals.

progesterone

testosterone

Likewise, Bryan observed increases in progesterone and testosterone with hunting pressure, perhaps as a result of disruption of pack dynamics brought on by excess mortality. In wolf societies, breeding females (the mothers) suppress reproductively mature subordinate females (usually their daughters) reproduction, resulting in a pack structure in which only the dominant female breeds. In packs with unstable social conditions, as when hunting removes individuals, this suppression of subordinate reproduction is interrupted, which could result in population-wide increases in sex hormone production.

Dr. Bryan also notes a possible confound in the comparison of the two groups: the tundra taiga wolves also differ in their ecology. These populations have much greater long-distance movements as they follow migrating herds of caribou, and the increased cortisol may reflect the stresses of these long-range movements.

Nonetheless, this study provides an fascinating glimpse at the inner lives of wolves. It will be very interesting to see what follows from this research, especially if we can determine how the hormonal state of populations influences their behaviour.

Well done, Sean.

Pingback: Morsels For The Mind – 05/12/2014 › Six Incredible Things Before Breakfast