Female Black-throated Antshrike. Photo by Phil Stouffer. What an impressively fierce-looking bird!

Remember my post last week on the White Woodpecker preying on wasp nests? Well,if you browsed that issue of Revista Brasileira de Ornithologia, you may have noticed that I published an article on a similar topic!

This is another account of a bird preying on wasp nests, one that was completely unexpected. This involved the Black-throated Antshrike, Frederickena viridis. Black-throated Antshrikes are members of the Thamnophilidae, or antbirds, a largely Neotropical family known for being associates of army ants. Basically, these birds “attend” army ant raids and parasitize the ant colony by quickly grabbing the insects, lizards and arachnids that flee the approaching ant swarm.

Eciton burchellii army ants. These impressive swarm raiding ants kick up quite a lot of prey from the leaf litter, which antshrikes are only too happy to steal.

During fieldwork in 2010, we caught a male Black-throated Antshrike is doing its own dirty work, striking wasp nests, causing the wasps to abscond, and feeding on the brood. Here is the video (edited for time, as the whole attack sequence lasted 42 min):

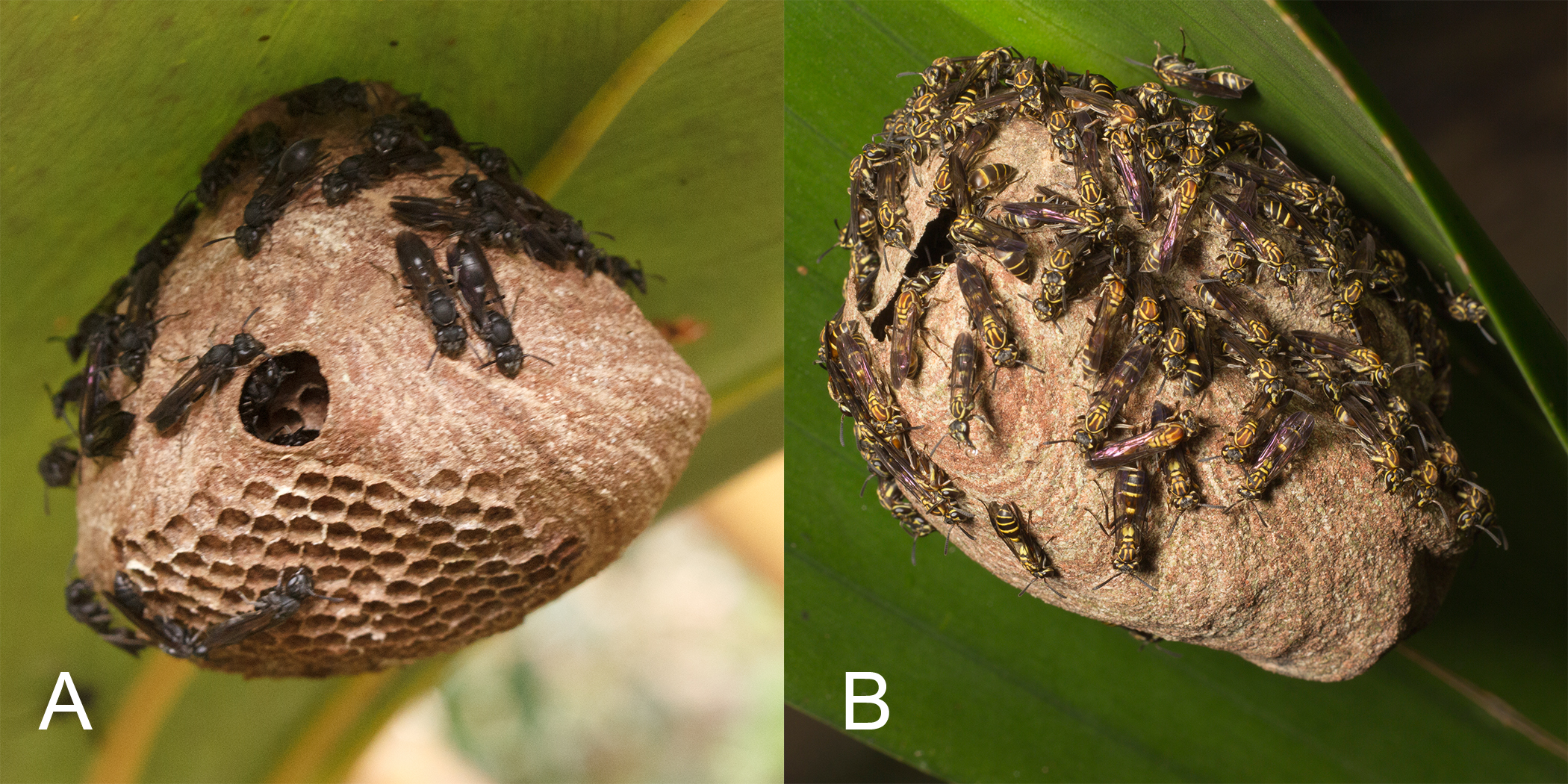

The two wasp species in question were Polybia scrobalis and Polybia bistriata, which we had placed in a video arena for our experiments documenting Red-throated Caracara feeding behaviour. In some ways, you could say that the antshrike was parasitizing us! This was all recorded as intended by our automated video system, which reacts to motion in the video stream and records the action with a 5-s pre-recording buffer. On that morning, my field assistant Tanya Jones and I were just getting up and having breakfast when this antshrike was attacking. By the time we were done breakfast, the antshrike was too!

A few things to note: Unlike their behaviour with the Red-throated Caracaras, this Polybia scrobalis colony fought back. At 0:30, 1:22 and 1:45 in the video, you can see wasps attacking the antshrike, and in the second two instances, the antshrike plucking off the wasps.

For comparison, here is an attack on the same wasp species by Red-throated Caracaras:

So why do the wasps attack the antshrike and not the caracaras? Can these wasps can evaluate the threat posed to the colony and adjust their defence/retreat appropriately? Maybe the wasps somehow evaluate the odds of successfully driving away a predator and abscond if nest defence is likely to be hopeless. After all, the workers which are killed in nest defence are still a loss. Continued defence piles up the losses, and if defeat is inevitable, it is better to retreat with your worker force intact.

Alternatively, it could be that the colony the caracaras attacked was worse off in some way, and more likely to abscond, but the possibility remains that wasp defensive behaviour against vertebrates is plastic. There is definitely room for some exciting research here.

Considering the White Woodpecker, the Black-throated Antshrike, and the Red-throated Caracara (among others) it seems that more and more vertebrate predators are being found that prey on wasp nests. In these cases, it appears that the birds are minimizing the risk of stinging by inducing the absconding response of their swarm-founding prey before moving in close to feed on the larvae.

While I was a little upset that these nests fell to the antshrike rather than giving me more data on caracara predation, getting a paper out of it and learning something new was well worth it.

Male Black-throated Antshrike. Photo by Phil Stouffer.