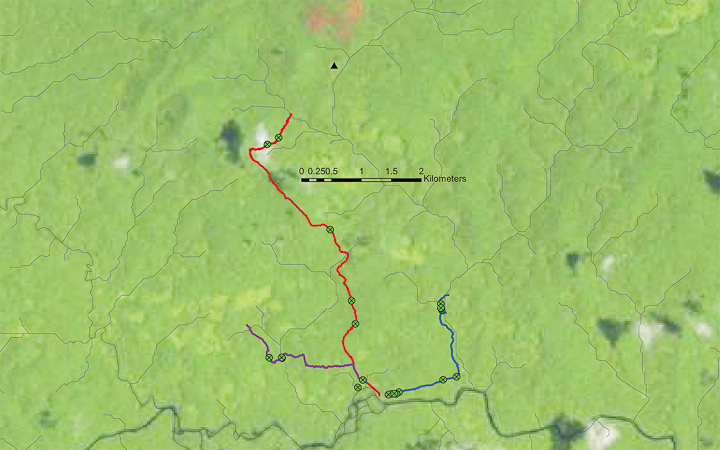

Compared to my time in French Guiana, I found that travel by river offers a much greater volume of observations than walking in the forest. When I was in French Guiana travelling trails on foot, I was lucky to encounter one example of a particular habitat in a day, but on the boat I could see the same type of habitat many times over. Needless to say, this was a great natural history lesson in the making.

One of the particular habitats we saw a lot of was the meanders of the river, where the river loops and bends around long curves. These bends form spontaneously via the action of vortices along curves in the river, and on the inside of each curve there is high deposition of silt (on the outside is a high level of erosion). This is the process by which oxbow lakes are formed. The result is that the inside curve is an area that was formerly river-scoured, but now has abundant new soil. Within these areas are a sparser forest, dominated by a few fast-growing tree species such as Cecropia and Triplaris (called “Long John” in Guiana). These are habitats that harbor a beautiful example of tropical symbiosis.

Yellow-rumped Caciques (Cacicus cela) bathing together in the early evening. These are highly social birds with colonial nesting.

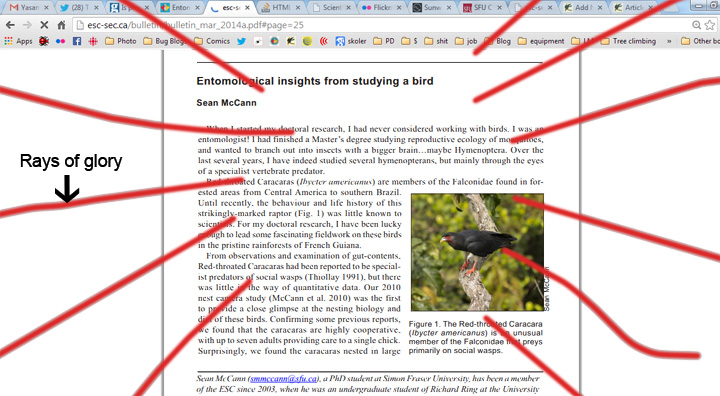

One of the first things that I noticed about these meander forests is that they more often than not contained a large colony of nesting Icterid birds, either Green Oropendolas, or Red-rumped or Yellow-rumped Caciques, with the latter being the most common. All of these birds are known to preferentially nest in association with large, aggressive wasp species, such as Polybia rejecta and Polybia liliacea. This is thought to benefit the birds in two ways. Number one is that the wasps can help dissuade nest predators, such as monkeys. Number two is that populations of predaceous wasps may reduce the parasite burden (particularly parasitic Philornis flies) that the nestlings endure.

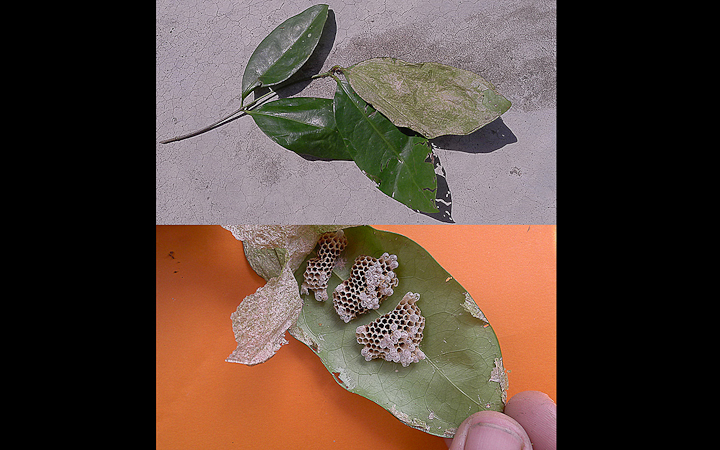

A colony of Cacicus cela nesting in association with Polybia liliacea. We also saw them with Polybia rejecta and Epipona spp. wasps.

In turn, the wasps nest in these particular trees for a reason. They nest in trees that are occupied by Azteca ants, a type of dolichoderine ant that basically owns the tree, with large carton nests containing perhaps millions of moderately small workers and hundreds of queens. The wasps nest here because the Azteca repel one of the wasps’ worst enemies: army ants. Although army ants (Eciton burchellii and Eciton hamatum) vastly outweigh the Azteca individually, the Azteca, by virtue of their overwhelming numbers, can keep army ant columns from advancing quickly up the tree (Servigne 2003). As army ants are all about blitzkrieg, and quickly stripping an area of profitable prey (Kaspari et al. 2011), they have learned to avoid the Azteca trees, which would take a protracted guerilla campaign to overcome. It has been recently shown that the wasps in turn benefit the ants, helping to repel some of their predators, such as woodpeckers (Le Guen et al. 2015)!

In examining again and again the morphology and placement of the nests in these associations, I was struck by a thought: perhaps the birds are also a net benefit to the wasps and the ants as well! I know from my research how formidable Red-throated Caracaras are in destroying wasp nests….What if these large numbers of nesting caciques help protect the wasps from the caracaras? It is not so outlandish a hypothesis, as the large nesting aggregations of caciques have been shown to mob bird nest predators such as monkeys and Black Caracaras and drive them away (Robinson 1985). Perhaps the Red-throated Caracaras may be driven away as well by large numbers of defensive caciques.

I was amazed by the numbers of large wasp nests we encountered at these sites, in stark contrast to the relatively low numbers I encounter in normal forests. It is not just the presence of ants which is keeping these nests safe, as Azteca occur in large numbers all over the forests. I think something else is going on here to help protect these wasp nests, and I bet it is the birds. Anyway, I would love to go and study this sometime, but this story just reinforces to me the inspiration that I only get by going to the field.

The Black Caracara, a known predator of cacique nests, is sometimes mobbed and driven away by Yellow-rumped Caciques.

References

SERVIGNE, P. 2003. L’association entre la fourmi Azteca chartifex Forel (Formicidae, Dolichoderinae) et la guepe Polybia rejecta (Fab.) (Vespidae, Polistinae) en Guyane Française. Universite Paris-Nord.