This is the illustration of the Petit Aigle d’Amerique from “Planches enluminées d’histoire naturelle” 1765

I mentioned last week in my introduction to the Red-throated Caracara that there is very little known about the species. While details of the life history of these birds are still hazy, the existence of the bird has in fact been known to scientists for quite a long time. To know a species, we must first be able to recognize it as distinct and to give it a name. There is a formal protocol for this, that has been developed and refined through time, and it so happens that the Red-throated Caracara has a long history in zoological classification. I normally find the subject of early nomenclature work to be a bit dry, but I am pleased to report that work with the Red-throated Caracara has been a surprisingly pleasing visual endeavour from the outset.

The first published description that I can find on these caracaras belongs to Buffon, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon to be exact, one of the pioneering Enlightenment era naturalists. Buffon’s 1765 description consisted of an engraving and a name, “Aigle d’Amerique” in the “Planches enluminées d’histoire naturelle“, a 24 volume set of coloured engravings done mainly by F.N. Martinet, a talented engraver. This work was commissioned by Buffon and supervised by Daubenton, so authorship is a bit muddled, but on the whole, the work is mainly attributed to Buffon. He recognized this species as an eagle, rather than a falcon, as he considered the shape of the bill, down turned at the end, to be more eagle-like.

Drawing inspiration directly from Buffon/Martinet/Daubenton’s work, the first written description seems to be that of an Englishman, one John Latham, who described the bird quite well and called it “the Red-throated Falcon” on page 97 of his 1781 book “A general synopsis of birds“. It is unclear why Latham placed this species with the falcons, although he was quite correct to do so.

Here is Latham’s original description, which gives the name Red-Throated Falcon, and notes the occurrence of the species in Cayenne and other parts of South America

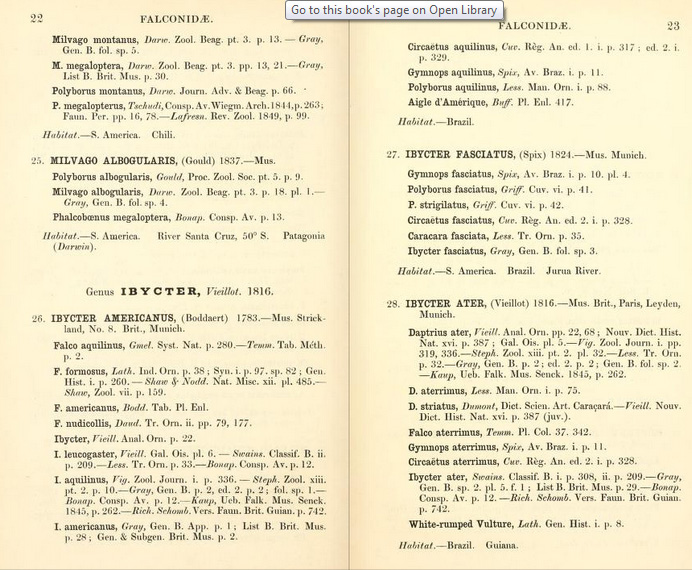

While this is a step along the path, it was not yet the official scientific name of the Red-throated Caracara…Latham’s description may have been useful, but it is not considered the first official species description. That honour goes to Pieter Boddaert, who, in 1783 gave this species its first Latin binomial: Falco americanus in “Table des planches enluminéez d’histoire naturelle de M. D’Aubenton: avec les denominations de M.M. de Buffon, Brisson, Edwards, Linnaeus et Latham, precedé d’une notice des principaux ouvrages zoologiques enluminés“. As the species name “americanus” now has precedence, it has remained attached to the Red-throated Caracara to this day.

In 1786 Gmelin (who was an associate of Carolus Linnaeus) named it Falco aquilinus, but this is considered a junior synonym, as it was published after Boddaert’s F. americanus.

In 1816 L.P. Vieillot moved this species to “Ibycter” in “Analyse d’une nouvelle ornithologie élémentaire“. This was the first written communication that applied the genus name “Ibycter” to the Red-throated Caracara, which has more or less stuck, and also a new common name “Rancanca” which has not. I am very intrigued by the origin of the name Ibycter…I have not found what it refers to, whether to mythology or if it is just an obscure word…Anyone out there have some insight?

The first real natural history information on the Red-throated Caracara comes from 1834, with the publication of “La Galerie des Oiseaux“, also by L.P. Vieillot. Delightfully, “La Galerie” also includes an image of the species!

Lithograph from Galerie des Oiseaux featuring the Red-throated Caracara. This is presumably attributable to Godefroy Engelmann, a lithographer based in Paris.

In addition to the new name, Ibycter Leucogaster, Vieillot contributed some real natural history to the scientific record, noting their loud calls and group living habits. In addition, having read Vieillot for the first time last week, I was shocked to read his statement that these caracaras are “ordinarily accompanied by toucans”. This habit, which apparently earned them the local name “Capitaines des gros-becs (Toucan Captains!), is not just some 19th century BS either, it was also made by Thiollay in his 1991 paper.

Thiollay noted several species that could be described as toucans accompanying the caracaras: The Guiana Toucanet Selenidera culik, Black-necked Araçari Pteroglossus aracari, Green Araçari Pteroglossus viridis, Channel-billed Toucan Ramphastos vitellinus and the Red-billed Toucan. The latter species was the one most commonly found accompanying the Red-throated Caracaras. But we get ahead of ourselves. Let us stay in the first half of the 19th century, shall we?

Red-billed Toucans often do follow Red-throated Caracaras. They also sound like a small dog barking.

In 1838, the first popular work to mention this species was published. The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge published their Penny Cyclopaedia with the express (and proto-socialist) idea to bring scientific knowledge to the working classes. This was kind of like the Wikipedia of 19th Century Britain. Here is their entry (with an illustration!) for the Red-throated Caracara (on the bottom right). This is part of a much larger section of falcons in general, and is quite commendable for its completeness.

![The penny cyclopædia [ed. by G. Long].](http://ibycter.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/the_penny_cyclopc3a6dia_ed_by_g_long-176.jpg?w=569)

This brings us to the middle of the 19th Century. Darwin was just about to arrive back from his voyage on the Beagle, Wallace was yet to set sail for Pará (where he would collect a Red-throated Caracara!), and the world of natural history was yet to be turned on its head by the revelations of Natural Selection as formulated by these two.

I am sure there are many taxonomic references I have left out that I could have usefully employed, but my attention must be elsewhere at the moment. I will return to the early world of ornithological literature, specifically the second half of the 19th Century at a later date. If you are eager to see a list of early synonyms and their references, look no further than page 22 of Strickland’s Ornithological Synonyms below.

This is the short early history of the scientific description for just a single species of bird. Of course, there are many many others who share a more or less parallel track through the literature. What I find fascinating is that I can do a few short hours of study on the internet and bring to you this history without even visiting a library or a museum. Thanks go out to the Internet Archive and the Biodiversity Heritage Library websites, who make trawling through and accessing this literature possible. An thanks to you for reading!

This is the short early history of the scientific description for just a single species of bird. Of course, there are many many others who share a more or less parallel track through the literature. What I find fascinating is that I can do a few short hours of study on the internet and bring to you this history without even visiting a library or a museum. Thanks go out to the Internet Archive and the Biodiversity Heritage Library websites, who make trawling through and accessing this literature possible. An thanks to you for reading!

![The penny cyclopædia [ed. by G. Long].](http://ibycter.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/the_penny_cyclopc3a6dia_ed_by_g_long-176.jpg?w=569)